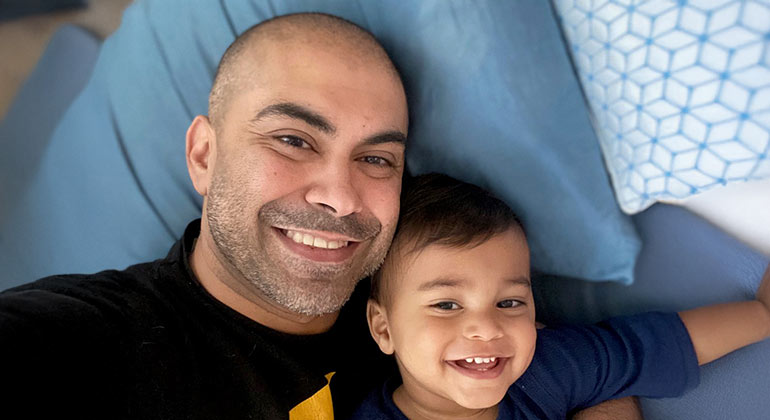

44-Year-Old Dad Survives “Widowmaker” Heart Attack

When Umair Qadeer’s son was born, Umair decided it was time to get proactive about his health: “It wasn’t just me anymore; I was now responsible for another person.”

Despite being healthy and active, Umair, 44, knew there were heart issues in his family, so he made an appointment for a full cardiology exam. The doctor performed a variety of blood tests and scans and proclaimed Umair healthy. “His exact words were ‘clean as a whistle,’” said Umair.

It was quite a shock, then, to have a “widowmaker” heart attack—the worst type—six months later. Thanks to quick thinking by Umair and his wife, Teju, and to top-notch care at Mount Sinai Queens’s Interventional Cardiology Lab, Umair is here today.

It was a balmy day in November 2024 and Umair was on a Citi Bike, rushing back to his Astoria home. He was surprised by how out of breath he got. “Google Maps said it should have taken me six minutes to get home but I made it in four, so I figured that’s why I was worn out,” he said.

When he walked in the door, he told Teju that he couldn’t seem to catch his breath but thought he’d be ok in a bit. He sat down to rest. When that didn’t help, he tried bending over, then lying on the sofa. But no matter what position he took, the pain kept getting worse.

“I didn’t want to be that guy who has a panic attack and calls an ambulance,” said Umair. But the pain in his shoulder got Umair thinking he might be having a heart attack.

“I remembered talking to a friend who had had a heart attack and he told me the whole progression of symptoms,” Umair recalled. “When it got to the shoulder, I realized I was probably more than just winded.” About 20 minutes after he got home, when the pain still hadn’t subsided, Umair called 911.

The ambulance arrived quickly and brought Umair to Mount Sinai Queens. In the ambulance, paramedics performed a test called an electrocardiogram (EKG), which let them see the electrical signals in the heart. “They told me I was having a heart attack,” Umair remembered. The team also used a Mount Sinai mobile app called STEMIcathAID for heart attack patients. The app tells everyone who needs to know all about the situation—doctors, nurses, and technicians to prepare the operating room, medicines, and equipment, and even security, to have the elevator waiting.

As soon as Umair arrived at the hospital, he was rushed to the catheterization lab, which performed an imaging test called a coronary angiogram. This test uses contrast dye and provides more detail than an EKG. That’s when Umair met interventional cardiologist Jonathan Murphy, MD, a heart surgeon specializing in coronary artery disease.

Dr. Murphy saw that Umair’s blockage was in his left anterior descending artery, the largest one carrying blood to the heart. And it was 100 percent blocked. This type of heart attack, called a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), is the most dangerous type, nicknamed “the widow-maker” because of the low survival rate. “Once we confirmed Umair had a true STEMI, we had to open the artery as quickly as possible, with a goal of having the artery open within 90 minutes of his first contact with EMS, in accordance with American Heart Association Guidelines,” explained Dr. Murphy.

They sedated Umair and gave him a local anesthetic, then Dr. Murphy performed a percutaneous coronary intervention to open up the blocked artery so the blood could flow again. To do this, he threaded a small tube called a catheter through Umair’s groin area and pushed it up through the artery. A small balloon at the end of the tube opened up the artery. Then Dr. Murphy inserted a small metal mesh tube, called a stent, to hold the artery open. The stent will stay in there permanently and will release medicine directly into the artery to reduce the risk of the artery closing up again.

Umair was conscious throughout the procedure. “When they were placing the stent, I had the feeling that I was going to fall asleep and just sort of let go,” remembered Umair. “But then I thought about my son and I heard him say “dada” in my head. That jolted me and made me realize I have to fight this, I have to stay awake and aware. My son cannot be the kid who only has stories but not memories of his father. That was a monumental moment for me.”

After the procedure, Umair spent two nights in intensive care, which is typical for a STEMI patient. His heart was operating at 42 percent (normal is 60 percent). He now takes several medications to lower his cholesterol and help his heart recuperate. He also gives himself an injection every two weeks.

At one month after he left the hospital, an echocardiogram showed his heart function had improved to 50 percent. “Clinically, he’s doing well,” says Dr. Murphy. “We expect him to continue to improve.”

Umair is back to his regular routine at work and at home—with a few tweaks. He has increased his walking, his main form of exercise; now he walks 80 to 100 miles a month. In fact, walking has become a form of meditation for Umair.

Umair is also more careful with his diet. “I don't eat a lot of red meat, I don't eat a lot of fried stuff, and I try to limit sugar as much as I can,” he said. But perhaps the best medicine is spending time with Teju and his mischievous little son.

“My son was born at Mount Sinai West, so I already had a good association with Mount Sinai. All the care I got at Mount Sinai Queens was great,” Umair said. “Dr. Murphy is fantastic. He has such a great bedside manner. He made me feel comfortable immediately. I mean, given the circumstances, I immediately felt like I was in good hands.”