Blurry Vision and Seeing Spots Could Be Eye Stroke, Not a Migraine

In December 2021, Dara Lehon, 47, thought she was having a migraine. But a few days later, when the vision in her left eye was still blurry and she was still seeing spots, Dara went to the doctor. To her surprise, she found that she had a retinal artery occlusion—an eye stroke—that was caused by a hole in her heart.

It was too late to repair some of the damage to Dara’s eye, but specialists at The Mount Sinai Hospital acted quickly to fix the hole in her heart and make future strokes far less likely. By late spring 2022, Dara was getting back to work and her active life, and she was eager to raise awareness about eye strokes. While the condition is rare, it requires prompt treatment, like all strokes. Anyone who suddenly sees spots or has blurry vision should see a doctor immediately, Dara says.

Before her medical journey began, Dara had always made health a top priority. She jogs regularly and avoids red meat. With no reason to worry about her health, Dara assumed the blurriness and spots in her vision were related to migraines she had long suffered, sometimes seeing ocular auras. “I didn’t stress out about it too much because I’ve had migraines since my 20s,” Dara told the Today website. “I saw some weird spots in my eyes, and it looked a little blurry, and I figured I was tired.”

Auras are often described as crescents or zigzags marching from the outside of the vision in, or flashes of light known as scintillations of vision. However, the symptoms of a stroke do not fade with time like those of a migraine aura.

When Dara’s symptoms were still there a few days later, a friend urged her to see a doctor. Dara was nervous about going to a doctor while the omicron variant of COVID-19 was surging. Fortunately, Dara’s friend was persuasive. The first doctor she consulted saw bleeding in her eye and suggested she see a retina specialist.

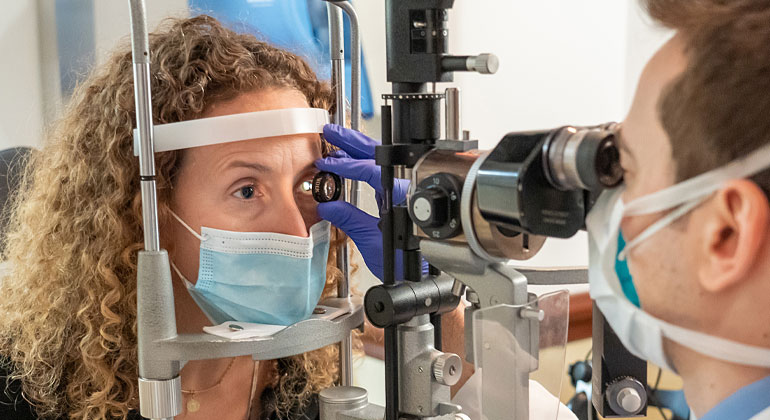

In January 2022, Dara was being treated at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai, by Alexander Barash, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology and retina specialist, who found that Dara had an eye stroke. “The typical way this presents is painless vision loss. It is in one eye—and not both at the same time. People say their vision is ‘hazy’ or ‘blurry’ as part of their vision appears blocked,” says Dr. Barash. “This is a problem of the patient’s circulatory system that happens to affect the eye. It could have happened anywhere, including causing a stroke in the brain, for example, by the same process.”

People who smoke or have cardiovascular disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol are at higher risk for eye stroke, Dr. Barash says. Dara ticked none of those boxes. “This is wild,” she said. “I can’t believe this is happening to me. I have low blood pressure, if anything. I’m active.”

Once he diagnosed the condition, Dr. Barash sent Dara to the emergency room for a complete work-up, including blood tests, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). “They wanted to make sure there was no brain damage,” Dara explained. The medical team also performed an echocardiogram bubble study, in which saline with bubbles is injected into a vein in the arm, and the movement of the bubbles is used to look for abnormal movement of blood from one side of the heart to the other. The bubbles moved from the right side of Dara’s heart to the left, which suggested she had a hole in her heart called a patent foramen ovale, or PFO.

PFOs are relatively common. When babies are developing, they have a flap-valve connecting the two upper chambers of the heart. The flap closes at birth and seals shut in most people, but in about one-third of adults, the trapdoor, or PFO, persists. PFOs are usually harmless. But when a young person has a stroke, doctors often find the person also has a PFO.

“When people have a stroke for no apparent reason, we find the PFO more often than we would find in the general population. And these people are also much more likely to have a second event,” says Barry Love, MD, Director of the Congenital Cardiac Catheterization Program at The Mount Sinai Hospital. “A small clot that forms in the legs that otherwise would go to the heart and go to the lungs and be harmlessly filtered out, may go across a PFO to the left side of the heart and travel anywhere in the body.”

If the clot goes to the brain or the eye—as in Dara’s case—it can cause stroke there. “The eye is actually part of the brain, and if a clot blocks an area of blood flow, you get immediate vision loss,” Dr. Love says. “If it breaks up, the flow is able to go around, and the vision is then restored.”

To prevent her from having another stroke, Dr. Love fixed the hole in Dara’s heart. In the procedure he threaded a catheter through a vein at the top of Dara’s leg up to her heart, then he placed a “little plug” in the hole to close it. “Then the tissue of the heart grows over it to seal it up,” Dr. Love says.

Since the procedure, Dara has been trying to get back to normal. That means going back to work, eating healthily, and exercising. “I use running as one of my gauges,” she says. “I’ve been increasing my mileage basically every week. I get out of breath much sooner. It’s harder to rebuild.” But she’s happy with her progress.

Dara wants to take her experience and use it to inform others about eye stroke and its symptoms—blurry vision and seeing spots. Before December 2021, “there was no way I would have known what eye stroke was,” Dara says. “Calling a retinal artery occlusion a stroke actually helps elevate awareness about it and can potentially help people save their eyesight.”