Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence is the uncontrollable loss of urine. In women, urinary incontinence has three main causes: a weak sphincter, involuntary bladder contractions, or a fistula (abnormal connection between the bladder and the vagina).

Incontinence due to a weak sphincter is called stress urinary incontinence (SUI). SUI only occurs when you cough, sneeze, bend or lift, run, or do other kinds of exercise. It is like a leaky faucet. The most common cause of SUI is pregnancy and childbirth but it also may occur after certain operations like hysterectomy, or just from getting older. The most effective treatment for SUI is surgery (discussed below), but some patients can be successfully treated with behavior modification, physical therapy, and/or medications.

Involuntary bladder contractions cause incontinence because you actually start to urinate without control. The most common symptom is called urge incontinence (UUI). This is characterized by a severe and uncontrollable feeling of the need to urinate which causes you to rush to the bathroom, but if you don’t get there in time, you lose control and wet yourself. There are many possible causes of UUI including bladder infection, hormone deficiency, vaginal prolapse (dropped bladder), and neurogenic bladder due to diseases like multiple sclerosis and Parkinsonism. There are many treatments for UUI depending on the cause, but in the vast majority of patients, treatment is initiated with behavior modification, physical therapy, and medications. Only when these fail is surgery even considered.

Fistulas are very uncommon causes of urinary incontinence. There are only a few causes: 1) prior pelvic surgery, most commonly hysterectomy (removal of the uterus), 2) pelvic radiation for cancer, and 3) complications of childbirth or other forms of trauma like motor vehicle accidents.

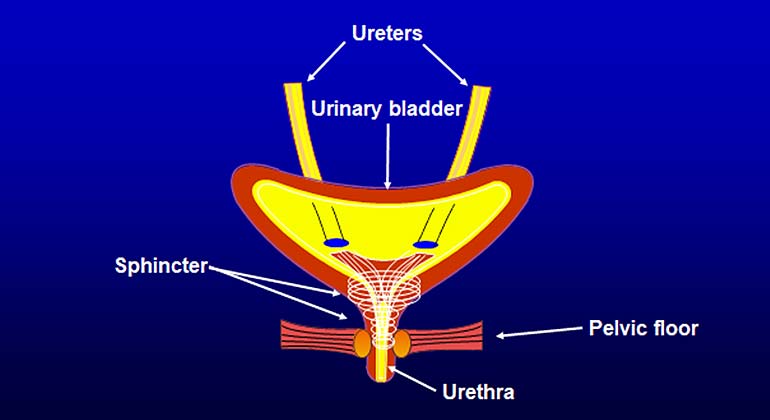

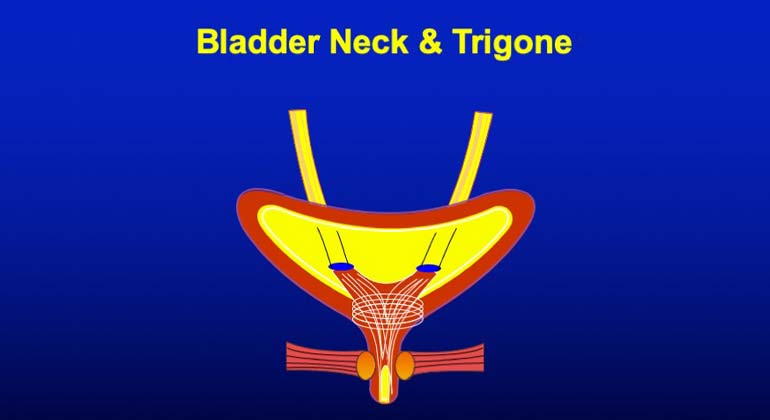

Stress Incontinence: Stress incontinence is caused by a weak urinary sphincter. The urinary sphincter is a specialized structure which lies in the wall of the urethra (the muscular tube through which you urinate); its function in both sexes is to maintain urinary control.

Normally, the urinary sphincter is kept closed in large part by contraction of the muscles inside and around the urethral wall. During urination these muscles relax and open, allowing urine to pass through. If the muscles have become damaged or weakened, they do not stay tightly closed and incontinence can occur.

In women, because the sphincter is naturally much weaker than in men, incontinence is much more common. It occurs, in part, because of repeated stretching and damage to the nerves and muscles of the sphincter during pregnancy and childbirth, and in part because of the effects of gravity, which tend to make the vaginal muscles sag and weaken. In mild cases, SUI is treated with behavioral techniques and/or light pads. In more severe cases, SUI is usually treated with sling surgery.

Sling surgery involves supporting the urinary sphincter with a hammock-shaped structure composed of either your own tissue, an artificial plastic-like material called a mesh sling, or tissue from a human or animal donor. The most common type of sling performed in the United States is a mesh sling, but in our opinion, the mesh sling sometimes involves complications that are very difficult to treat and that do not occur very often with the other types of slings.

Bladder Sling Surgery Without Mesh (Natural Tissue Sling)

Bladder sling surgery is a well-established procedure that works well; serious complications are rare. Jerry Blaivas, MD, Professor of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, pioneered the use of natural tissue slings. He has also written numerous peer-reviewed articles and book chapters on the subject and has lectured worldwide.

The operation that Dr. Blaivas performs is called the autologous rectus fascial pubovaginal sling, uses a strip of your own tissue called fascia (the lining of muscle) as the sling instead of a synthetic (man-made) mesh. Using your own tissue means there is no possibility of rejection, erosion, or any of the serious complications associated with mesh. The fascial sling is considered a gold standard for the treatment of stress incontinence in women today.

The procedure takes about an hour and a half and can be done with either general or spinal anesthesia. It is done through a small incision in the lower abdomen, below the pubic hairline so the scar is usually not visible. A second small incision is made in the vagina; it usually becomes unnoticeable in a matter of months. Postoperative pain is relatively minor and usually does not require the use of narcotics. Most patients stay in the hospital one or two days and leave without a catheter, although about one in three patients need to use a catheter temporarily, usually for only a few days. Peer-reviewed studies have shown that fewer than 1 percent of Dr. Blaivas’ patients with uncomplicated SUI develop a blockage from the sling that requires another surgery or catheter to correct, far better than the national average (about 7 percent); and the rate of developing urge incontinence (3 to 5 percent), described above, is less than half of what other surgeons report.

Complications of Vaginal Mesh Slings for Incontinence

Surgery that uses a synthetic mesh is the most common operation done to correct urinary stress incontinence in women, but may lead to complications or failure. Dr. Blaivas is an expert on reconstructive surgery for patients with significant mesh complications. He has published the largest series of reports in the world on women who have undergone urethral reconstruction—a procedure that can help patients whose urethras were damaged by mesh surgery—and the largest series on treating urinary fistulas after mesh sling complications.

Mesh complications may cause new symptoms that were not present before the surgery. They may include:

- Difficulty urinating or inability to urinate at all (urinary retention) due to a blockage by the sling

- Urinating too often and having to rush to the bathroom

- Urinary urge incontinence (having to rush to the bathroom and not getting there in time)

- Recurring urinary tract infections

- Pain (including pain during sex)

- Vaginal discharge or bleeding

- Bladder stones

- Ureteral obstruction (blockage in the tube between the kidney and bladder)

Difficulty urinating and urinary retention have two main causes: a blockage from the sling itself and/or a weak bladder. Sometimes it is just a temporary problem that will get better by itself. Treatment of a blockage depends on many factors. If the problem began immediately after the surgery, temporary treatment with a catheter may be all that is necessary while the body heals. If surgery is needed, it may be possible to loosen the sling with a very minor outpatient operation. If these things do not work (they usually don't), a more extensive operation will probably be necessary to cut the sling or remove part of it, or in severe cases, to remove the mesh entirely and reconstruct the urethra.

If the bladder muscle is too weak, you may not be able to urinate normally even if there is no blockage from the sling. The best treatment for this is for you to learn to insert a catheter to empty the bladder. It sounds gruesome, but it’s not, and just about everybody can do it without difficulty. Fortunately, this condition improves in most people within a month or so and then the catheter is no longer needed.

Urinary frequency and urgency—also known as overactive bladder—is most often caused by a bladder infection (cystitis), but it also can be due to a blockage from the sling or even from erosion of the sling into the urethra or bladder. Cystitis is treated with antibiotics. A blockage from the sling or erosion is treated surgically.

Recurring urinary tract infections and bladder infections are very common in women and may not be related to mesh surgery. Other causes include incomplete bladder emptying, urethral and bladder diverticula, and bladder stones, all of which can be treated, but if the mesh is causing the problem, surgery may be needed.

Pain can be in the lower abdomen or vagina. It may be constant, or only present during urination or sex. Painful sex is called dyspareunia. It may just be the result of normal healing, which results in scar formation, or it may be due to the mesh. Treatment depends on the particulars of your situation and could involve anti-inflammatory or pain medications, physical therapy, trigger point injections, myofascial release (massage therapy), or even surgery to remove the mesh. Unfortunately, refractory pain (pain that does not get better after multiple treatments) occurs in about 4 percent of women and dyspareunia in 7 percent after sling surgery. These complications can have a significant negative impact on quality of life.

The cause of vaginal discharge or bleeding is usually apparent on examination. Most of the time it is an infection that can be treated by medication, but it can also be due to erosion of the mesh into the vagina. Depending on the degree of erosion, patients may need only topical hormones or minor outpatient vaginal surgery, or they may need vaginal reconstruction.

Bladder stones are almost always due to erosion of the mesh into the urinary tract and, if that is the case, surgery will be necessary to remove the stones and the mesh. Ureteral obstruction (blockage to the kidney) is a rare complication of slings that occurs when the mesh is passed into or too close to the ureter. The only treatment is surgical.