A Year After Bicycle Crash, Resilient Young Man Walks Again With Support of Mount Sinai’s Rehabilitation Team

In October 2020, Cory Moses was riding on his bike to join his then-girlfriend for Sunday brunch. The 25-year-old never made it to meet her. Only two blocks away, someone opened a parked car door, and he was flung into the path of a moving truck. Cory suffered six fractured ribs, two broken arms, and a fractured spine, which caused paralysis.

"The lower half of my body was at a weird angle, and I definitely knew something was wrong." Cory told Good Morning America.

Cory underwent three spine surgeries at a Brooklyn hospital and had two rods and eight screws inserted into his spine to try to stabilize it. He then spent two weeks in intensive care. He was warned he might never regain the use of his legs, but a slight movement in his right leg suggested that he might recover some minor mobility over time.

Unfortunately, by December 2020, the screws in Cory’s spine were beginning to destabilize. He sought out treatment at Mount Sinai, and under the supervision of Konstantinos Margetis, MD, PhD, Director of Complex Spine Surgery for the Department of Neurosurgery at The Mount Sinai Hospital, he underwent two final surgeries that successfully stabilized his spine.

After the surgeries, Cory was admitted to the inpatient center at the Department of Rehabilitation and Human Performance. He received intensive physiotherapy for more than two months, including treatment using a powered exoskeleton at Mount Sinai’s Exoskeleton Walking Program. The Mount Sinai Health System is one of only a few in the United States to offer an exoskeleton program. These external devices are attached to the legs and help build muscle strength and promote neuroplasticity (where the brain and spinal cord adapt or create new neural pathways) to help patients relearn the ability to stand and, in some cases, to walk again.

“Within my first week or so at Mount Sinai I got myself into a place of peace and an understanding that if I’m going to get out of the hospital and into rehab that my mind and my focus has to be there. I can't lose that to my feelings or depression," Cory said.

Cory was discharged in January 2021 to spend a few months recuperating and to learn to adjust to using a wheelchair. By the time he returned to The Mount Sinai Hospital’s outpatient rehabilitation center in April, he had made significant progress and was able to walk short distances at home in his apartment unassisted.

Liz Pike, PT, DPT, NCS, Master Clinician, Mount Sinai Rehabilitation Center, was a key member of the team Cory worked with. "It takes a lot of time for the body to heal just from a neurological injury, and he put in the work and really listened to his body, did all the steps, and built the foundation blocks to get to the bigger movements, like walking and balancing," she told Good Morning America.

From the time of the accident to his ongoing recovery, Cory has showed an extraordinary amount of mental resilience. He says he realized early on that despite the severity of his injuries, his own mental strength would be key in helping him make the best recovery possible.

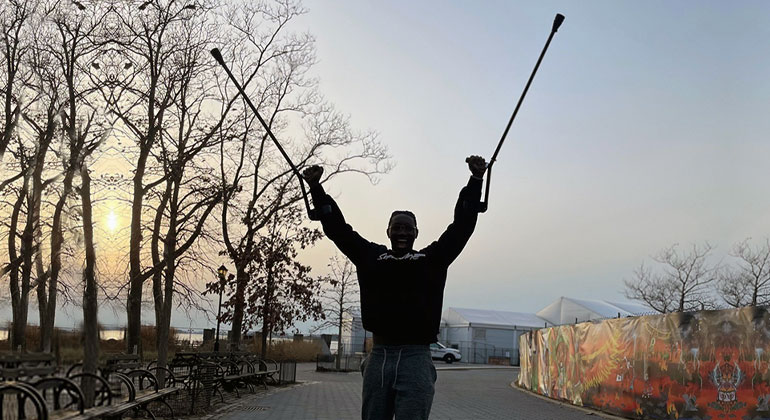

Cory still uses crutches and leg braces up to his knees, but he can walk as far as 1.5 miles. He has also set his sights on a new challenge—competitive parafencing. Thanks to the support of his friend Curtis McDowald, a member of the U.S. Fencing team for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, he has trained at a facility in New York City. He has already won two medals in California and now aims to compete in the Paralympic Games.

Angela Riccobono, PhD, Assistant Professor, Rehabilitation and Human Performance, is a psychologist and director of rehabilitation psychology at Mount Sinai. She was impressed by Cory’s response to the uncertainty and challenges ahead of him.

"Cory is such a special young man. I've been doing this job for almost 30 years, and I've never met anybody like him," Ms. Riccobono told USA TODAY. "After an injury like this, many people become overwhelmed by the uncertainty. But instead, Cory embraced uncertainty as an opportunity for growth. He didn't define himself by his limitations, but by his possibilities—at such an early stage in a traumatic injury, it was profound."