Out of the Dark

Living with dystonia can be very limiting, but thanks to innovation in deep brain stimulation, it doesn’t have to be

The day-to-day struggle with dystonia

When describing her daughter’s day-to-day struggle with dystonia, Alicia Hidalgo has an enlightening comparison: “Having dystonia is kind of like sitting in the dark. You just can’t see the world in the same way when you’re constantly battling your limitations.” Suelai Hidalgo started showing symptoms of the neurological disorder at the age of 3, when she consistently lost balance due to dizzy spells. Her parents took her from doctor to doctor in hopes of finding the cause of their daughter’s deteriorating functioning. At 14, the answer finally came – dystonia.

There are several different kinds of dystonia. Suelai was diagnosed with myoclonic dystonia, a genetic form of dystonia characterized by involuntary jerk-like tics, affecting the neck, shoulders, trunk, arms, and her voice. This neurological movement disorder prompts involuntary, repetitious muscle contractions, causing spasmodic gestures, and abnormal postures. While there is no known cause at this point, researchers have linked dystonia’s onset to faulty communication between the nerve cells involved in muscle contractions. It is primarily treated with a myriad of medications; however, the benefits of the drugs tend to wear off over time.

There are several different kinds of dystonia. Suelai was diagnosed with myoclonic dystonia, a genetic form of dystonia characterized by involuntary jerk-like tics, affecting the neck, shoulders, trunk, arms, and her voice. This neurological movement disorder prompts involuntary, repetitious muscle contractions, causing spasmodic gestures, and abnormal postures. While there is no known cause at this point, researchers have linked dystonia’s onset to faulty communication between the nerve cells involved in muscle contractions. It is primarily treated with a myriad of medications; however, the benefits of the drugs tend to wear off over time.

Despite the debilitating nature of the disorder, Suelai’s family encouraged her to live the most normal life possible. She went to a mainstream school with the assistance of an aide, graduated, and moved on to college-level courses. Yet even with medication, Suelai could not do many of the activities that her peers took for granted. Drinking from a regular cup, wearing “cool” clothes, and going out without supervision were impossibilities due to the unpredictable spasms. “She couldn’t do what most kids could do,” Alicia told the Mount Sinai team. “That is hard to accept as a mother. You want the best for your child.” Though going to school had its challenges, Suelai worked hard and kept up with her peers. “She definitely makes the best of what she has.”

Finding the down-to-earth surgeon

It was Suelai’s resilient determination that led her to consider deep brain stimulation (DBS). Suelai first heard about DBS in a magazine article, and after meeting a dystonia patient who had undergone the procedure, she started thinking about the treatment for herself. After further research and discuss this with her parents, Suelai scheduled a consultation with Mount Sinai neurosurgeon, Brian H. Kopell, MD, Director of the Center for Neuromodulation. Right away, Suelai felt at ease with Dr. Kopell. “He made her feel comfortable every step of the way,” says Alicia. Some of the steps Dr. Kopell took to ensure Suelai and her family’s comfort included a “question and answer” session about the possible outcomes of the procedure. “He treated us like human beings,” explains Alicia. “That’s how he is—down-to-earth.”

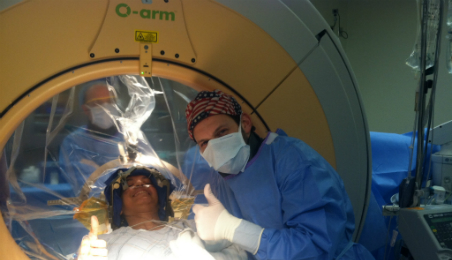

DBS is a two-part process. First is the surgical process, which involves three procedures, done by a neurosurgeon, followed by the programming, done by a neurologist. After each of her surgeries, Suelai was able to go home the next day.

Following her final procedure, Suelai saw her neurologist a number of times to have her simulator adjusted. She continues to attend postoperative programming to increase the efficacy of the treatment. “She had a positive outlook throughout the entire procedure,” recalls a Mount Sinai nurse.

Turning on DBS is like turning on a light

Since undergoing DBS, Suelai has been doing everything but sitting in the dark. As her follow-up programing continues, she is able to decrease the number of medications needed to manage her dystonia. Now she looks forward to going out with friends, eating at restaurants, and being more independent. Alicia is happy to see her daughter being able to do what she wants to do without constant supervision. “This technology is like turning on a light. Without it, having a movement disorder is like sitting in the dark, but with it…you can see the world.”