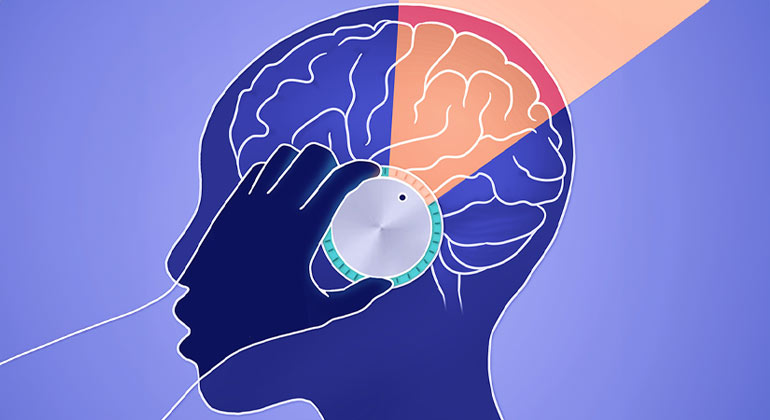

New Study Examines Impact of Violent Media on the Brain

Exposure to violence has a different effect on people with aggressive traits

With the longstanding debate over whether violent movies cause real world violence as a backstop, a study published today in PLOS One found that each person’s reaction to violent images depends on that individual’s brain circuitry, and on how aggressive they were to begin with.

The study, which was led by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the NIH Intramural Program, featured brain scans which revealed that both watching and not watching violent images caused different brain activity in people with different aggression levels. The findings may have implications for intervention programs that seek to reduce aggressive behavior starting in childhood.

“Our aim was to investigate what is going on in the brains of people when they watch violent movies,” said lead investigator Nelly Alia-Klein, PhD, Associate Professor of Neuroscience and Psychiatry at the Friedman Brain Institute and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “We hypothesized that if people have aggressive traits to begin with, they will process violent media in a very different way as compared to non-aggressive people, a theory supported by these findings.”

After answering a questionnaire, a group of 54 men were split by the research team into two groups—one with individuals possessing aggressive traits, including a history of physical assault, and a second group without these tendencies. The participants’ brains were then scanned as they watched a succession of violent scenes (shootings and street fights) on day one, emotional, but non-violent scenes (people interacting during a natural disaster) on day two, and nothing on day three.

The scans measured the subjects’ brain metabolic activity, a marker of brain function. Participants also had their blood pressure taken every five minutes, and were asked how they were feeling at 15 minute intervals.

Investigators discovered that during mind wandering, when no movies were presented, the participants with aggressive traits had unusually high brain activity in a network of regions that are known to be active when not doing anything in particular. This suggests that participants with aggressive traits have a different brain function map than non-aggressive participants, researchers said.

Interestingly, while watching scenes from violent movies, the aggressive group had less brain activity than the non-aggressive group in the orbitofrontal cortex, a brain region associated by past studies with emotion-related decision making and self-control. The aggressive subjects described feeling more inspired and determined and less upset or nervous than non-aggressive participants when watching violent (day 1) versus just emotional (day 2) media. In line with these responses, while watching the violent media, aggressive participants’ blood pressure went down progressively with time while the non-aggressive participants experienced a rise in blood pressure.

“How an individual responds to their environment depends on the brain of the beholder,” said Dr. Alia-Klein. “Aggression is a trait that develops together with the nervous system over time starting from childhood; patterns of behavior become solidified and the nervous system prepares to continue the behavior patterns into adulthood when they become increasingly coached in personality. This could be at the root of the differences in people who are aggressive and not aggressive, and how media motivates them to do certain things. Hopefully these results will give educators an opportunity to identify children with aggressive traits and teach them to be more aware of how aggressive material activates them specifically.”

This study was conducted with the additional partnership from researchers at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, SUNY, in Stony Brook, New York, and the Medical and Chemistry Departments at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York.

About the Mount Sinai Health System

Mount Sinai Health System is one of the largest academic medical systems in the New York metro area, with more than 43,000 employees working across eight hospitals, over 400 outpatient practices, nearly 300 labs, a school of nursing, and a leading school of medicine and graduate education. Mount Sinai advances health for all people, everywhere, by taking on the most complex health care challenges of our time — discovering and applying new scientific learning and knowledge; developing safer, more effective treatments; educating the next generation of medical leaders and innovators; and supporting local communities by delivering high-quality care to all who need it.

Through the integration of its hospitals, labs, and schools, Mount Sinai offers comprehensive health care solutions from birth through geriatrics, leveraging innovative approaches such as artificial intelligence and informatics while keeping patients’ medical and emotional needs at the center of all treatment. The Health System includes approximately 7,300 primary and specialty care physicians; 13 joint-venture outpatient surgery centers throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, Long Island, and Florida; and more than 30 affiliated community health centers. We are consistently ranked by U.S. News & World Report's Best Hospitals, receiving high "Honor Roll" status, and are highly ranked: No. 1 in Geriatrics and top 20 in Cardiology/Heart Surgery, Diabetes/Endocrinology, Gastroenterology/GI Surgery, Neurology/Neurosurgery, Orthopedics, Pulmonology/Lung Surgery, Rehabilitation, and Urology. New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai is ranked No. 12 in Ophthalmology. U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Children’s Hospitals” ranks Mount Sinai Kravis Children's Hospital among the country’s best in several pediatric specialties.

For more information, visit https://www.mountsinai.org or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

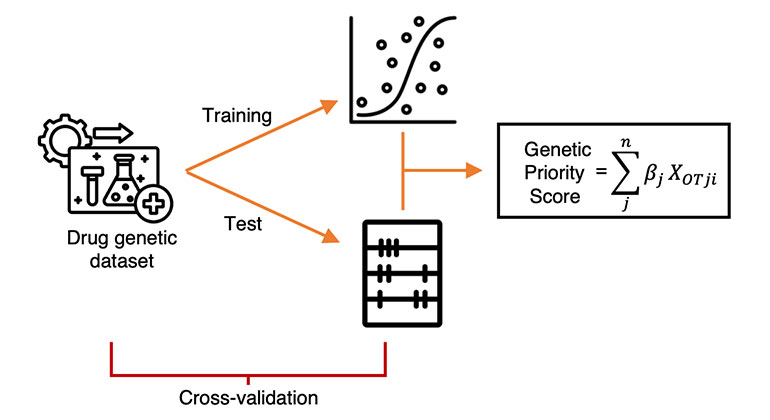

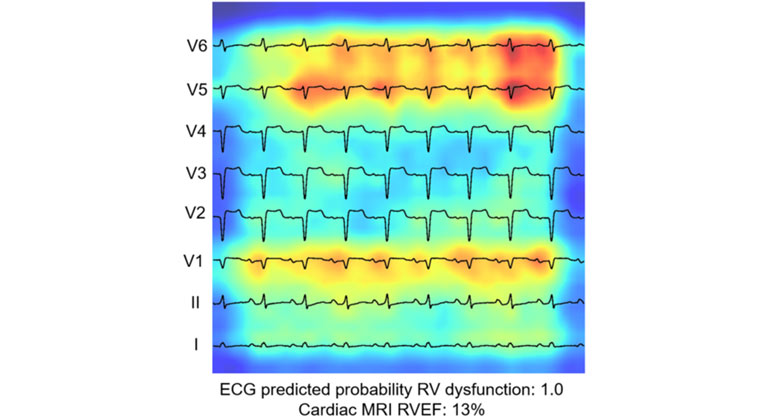

AI-Driven Study Redefines Right Heart Health Assessment With Novel Predictive Model

Jan 04, 2024 View All Press Releases

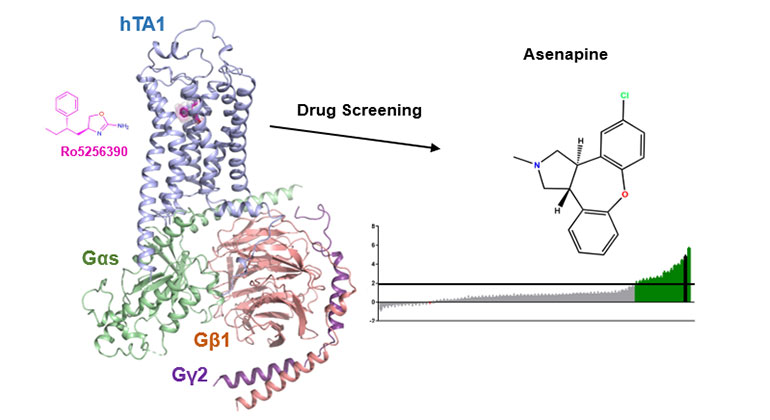

Demystifying a Key Receptor in Substance Use and Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Jan 02, 2024 View All Press Releases